UPDATED 16-Nov-2019

At today’s value of some $1,000+ for a single pickup some of the genuine original late 1950’s Gibson PAF’s are widely believed to be the best humbucker. People talk about it’s pleasing sound and endlessly discuss the sonic characteristics and how they relate to modern guitar playing. And it seems the whole pickup industry had become obsessed with producing vintage replicas. But is it really the best humbucker? Or has fascination with old and increasingly out-of-reach things whipped up a frenzy of exaggerated and emotive perceptions? So much so that a legend has been created without justification?

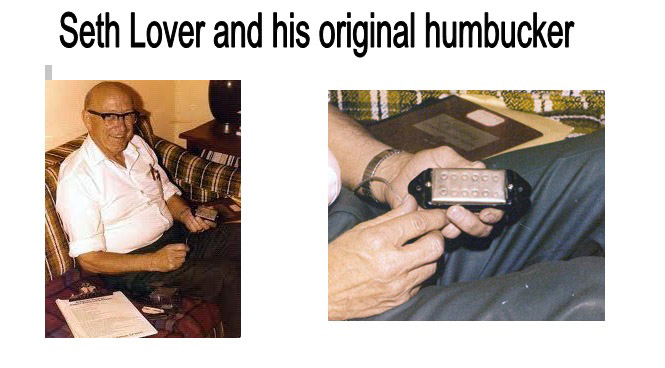

To get the right answer let’s begin with the question “Is there anything wrong with humbuckers?” Or to put it another way, is the design flawed and is there a better way to make a humbucker? When you understand that the inventing process was often more about mechanical convenience than by scientific investigation, all bets are off and the tantalizing possibility of vastly improved humbucker sound suddenly appears out of nowhere. Delving into the way Seth Lover invented his humbucking pickup for Gibson back in 1955 lends credibility of this idea.

All humbuckers exhibit certain undesirable characteristics mainly in the neck position that most guitar players are aware of. Ask any guitar player who has live stage experience with humbuckers and he will tell you that notes on the low wound strings and full chords on the neck pickup at high volume have no tone, sound sloppy, fluttery and untidy and somewhat unmusical. But many don’t complain because that’s just how they are and players develop techniques to mask or minimize the bad aspects of humbucker sound or simply just don’t go where it’s not nice.

This characteristic is known as flutter, farting or blurring … as in the notes (particularly the notes on the low wound strings played on the neck pickup) suffer loss of tone and definition and consequently become a fluttery, mushy blurr rather than a solid well defined note. This sounds bad enough on single notes but in the context of a full chord it is really quite unpleasant and unmusical and causes players to suspect their strings are not correctly tuned.

A related characteristic is lack of attack and dynamic range of the neck pickup. Compared to a P-90, which has loads of snappy attack and dynamic range on the neck pickup, a common humbucker is sadly lacking.

So why do other pickups not have this problem? The popular explanation is there is cancellation of certain crucial harmonics at the neck position but that explanation defies electrical physics because there is no mechanism for cancellation (other than a very narrow band of frequencies at 3KHz which can not be heard) only reinforcement. I understand when a string vibrates in the magnetic field of a humbucker each completed excursion of the string produces a sine wave with harmonics riding on the wave. There is some cancellation of the harmonics which occur at the precise wavelength of the distance (18mm) between the rows of poles at precisely 3KHz, but in the overall frequency plot this is not noticeable since the general plot has many peaks and valleys and these missing 3KHz frequencies blend into the background and go virtually unnoticed. There simply is no cancellation of such a width and magnitude that explains the murky sound of the low wounds of a humbucker and we must look elsewhere for the explanation.

During my experimental work with humbuckers I discovered a hitherto obscure (or unknown) Law of Electrical Physics that operates in the side-by-side coils of a Humbucker. It plays havoc with frequency content of the coils and is responsible for the compromised sound of the low wound strings, the same law also operates in Sidewinders but there it has more impact.

In order to understand why the problem exists it is helpful to go back in time to 1955 and follow the inventing and development process of Gibson’s original Humbucker and subsequently the activities of hundreds of replacement pickup manufacturers who mimic them. The following account is based on obvious facts but takes a degree of license to make a good read. Here we go ….. The year is 1955, it is 10am Tuesday morning and we are inside the Gibson factory at 225 Parsons Street, Kalamazoo, Michigan. The top brass inside Gibson are worried because of growing discontent among guitar players with Gibson’s P-90 because it is so darn noisy. Gibson’s best sounding pickup at the time was the P-90, possessing glorious sonic and dynamic attributes which remain unsurpassed by most modern pickups today, some 60 years on.

The pressure is on Gibson and President Ted McCarty has called Seth Lover into his office to brief him about eliminating 60Hz mains hum from their mainstay pickup, the P-90. McCarty hopes the P-90 can be redesigned to eliminate hum because the sound is great, it is relatively simple and cheap to manufacture (though not nearly as cheap as Leo Fender’s pickups) and has great versatility which makes it quite at home in all kinds of music. With the right amp and settings it can sound similar to twangy Strat, it can do smoky Jazz sounds and is bright enough for the country players, has wonderful attack and dynamic range and has a reasonable tight focused bass response … why sacrifice all that? What nobody knew in those days is that 40 years on the P-90 would also be one the best (if not the best) rock pickup …. if it were not for it’s Achilles Heel, the dreaded 60 cycle hum.

Ted McCarty is somewhat of a pickup designer himself, holding Patent # US2567570 A and a number of others concerning guitars and various hardware parts. But as president he is too busy to get his hands on this project and anyway, the technicalities of hum canceling is out of his league. However Seth has come to his attention as a somewhat capable pickup engineer.

There are several possibilities that explain the way Seth Lover went about the task, one makes an interesting story and fits with Ted McCarty’s own recollection of events and Seth’s down to earth pragmatic approach to solving engineering problems. Although Seth tells a slightly different story lets go loosely with Ted McCarty’s version.

Seth goes away and ponders the problem for a while, and then he remembers hearing something about Electro-Voice using a hum cancelling coil in their dynamic microphones. He wondered if the idea could be applied to a guitar pickup. So he makes a few inquiries and eventually uncovers 2 previous patents for humbucking pickups by other inventors years before. However these pickups did not use permanent magnets, instead they used electromagnets and thus have 3 coils and required an outboard power supply. So Seth try’s to get his head around the concept and dispense with the 3rd coil, the humbucking concept is a bit tricky and as we will discover later he devises several solutions but only one is successful. He assembles a sketchy idea of what is involved using permanent magnets and begins applying the principle to Gibson’s existing P-90 pickup as Ted McCarty had intimated.

Seth figures out that the redesigned P-90, in order to be hum canceling would have two identical coils arranged side-by-side. But how many turns of wire and what gauge wire would work? Also what dimensions should the bobbins be? What magnet could he use? So many questions, so many possibilities and so many experiments to be conducted and so many decisions to make. Seth has reservations about this approach since he knows all too well that changing the design of a pickup so radically will also change the sound, but just how radical will the change be? And will it be an acceptable outcome? The answers to these questions came fast enough as you will see.

As with all new technology it springs and evolves from, and is often based on present or established technology. The new pickup is to sound like a P-90 so looking for a fast and simple starting point that required little in the way of new parts and materials he reasons what better place to start than the P-90 itself. It seemed to be a better starting point than taking a stab in the dark.

I have a pretty strong hunch a lot more time and effort was spent by Walt Fuller in 1946 when he developed the P-90 in the first place. It’s coil shape/size and magnetic circuit had it’s origins in Gibson’s Charlie Christian pickup and yet it set sonic performance standards which are unrivalled by most any other pickup today. The P-90 is a brilliantly designed pickup but it’s Achilles heel is the copious amount of hum it generates which led to it’s downfall.

Gibson has all the parts on hand for the P-90 and that would not only save time but reduce the project and subsequent production cost as well. Alnico bar magnets, pole screws and magnetic collector bar, plastic bobbins and 42 gauge magnet wire …all those stock components are going to make his job much easier for all he has to do is modify a couple of P-90 bobbins and fabricate a base-plate to mount them on. This approach was very convenient in more ways that one, even the coil winder didn’t have to be reset for a different width bobbin because it was already winding 1/4" P-90 coils. Seth’s patent application certainly gives credence to this scenario because the drawings show a humbucking pickup housed under a P-90 Dog-Ear cover, and the core and coil height dimensions of the bobbins (1/4”) as well as the 42 gauge magnet wire are the same as for P-90 pickup. Note the similarities in these two illustrations.

.jpg)

An exploded P-90

An exploded humbucker

Seth realizes the bobbins could be fashioned simply by cutting the width of the flanges of a P-90 bobbin by half, utilizing the same ¼” high center piece but with reduced flange size. Each resulting bobbin would take half the 10,000 turns of a P-90 (i.e. 5000 turns on each one). Seth thinks that having the total number of turns of the P-90, the same Alnico bar magnet and essentially the same bobbin dimension (by virtue that, added together they equal one P-90 bobbin) that the new pickup will sound like a P-90, simply because all the important elements (equivalent dimensions and coil parameters) of a P-90 will be incorporated. It’s all so logical and predictable and would save him a lot of work.

Ideally the new pickup would be the same width as a P-90 so it would fit into a P-90 cavity. But because there are now 2 x 1/4” coil cores in the bobbins the new pickup will be at least 1/4” wider than a P-90 which has only one coil core. Seth’s humbucker turned out to require it’s own cover and it's own body cavity which is quite different to a P-90 cavity.

In an interview with Seymour Duncan in 1995 (https://www.seymourduncan.com/blog/latest-updates/seymour-w-duncans-interview-with-seth-lover) Seth freely admitted that he did not do any calculations or scientific experiments to determine coil parameters that would give the required frequency response, inductance and Q factor, he said the design of the pickup was more the result of mechanical and dimensional convenience and he simply filled the bobbins with as much wire as they would comfortably accept (turns out the be 5000 turns which is no coincidence since it’s half the number of turns of a P-90). And so it was that he set about the simple task of cutting the flanges of two P-90 bobbins to fashion 2 humbucker bobbins.

The P-90 has 2 Alnico bar magnets and the experimental pickup requires just one, so Seth is again pleased about saving money for the company by halving the expenditure on expensive Alnico magnets. The bobbins both have fixed poles to further save costs by eliminating the collector bars and machine screws (adjustable poles). The bobbins will be arranged side-by-side with a single Alnico bar magnet between them. It is all so beautifully convenient and much easier than making totally new bobbins.

Having eliminated the screw poles and the magnetic collector bar meant the steel slugs had to be big enough in diameter to contact the edge of the P-90 Alnico bar magnet (which was previously the job of the magnetic collector bar’s dual function as a spacer or gap filler). Fortunately the core of the bobbin is wide enough to easily accommodate a steel slug having 3/16 of an inch diameter which fits the dimensional architecture perfectly. That 3/16 inch dimension is no co-incidence either, the steel rod Gibson uses for truss rods is … you guessed it … 3/16 of an inch (4.76mm) diameter. So there is another material that Gibson has on hand that can be used in the production of the new pickup. One other reason Seth thinks this is good idea is since only one bar magnet is required for the humbucker (not 2 as in the P-90) the 3/16” steel slugs will conduct more magnetism to the strings and therefore increase magnetic efficiency and help to achieve the high output of the P-90, again minimizing the possibility of an objection from the powers that were at Gibson at that time.

This turns out to be a simple and cost effective solution and one that incidentally gave the new experimental pickup a different appearance to Gretsch's Filtertron humbucker.

One problem that was never solved properly and probably not so understood is the attachment of the coil termination leads. These are multi-strand wires coated in a Black plastic material. They are soldered to the two ends of the fine coil wires and taped over the sides of the coils. The problem is the bulk of these taped solder joins is squashed into the sides of the coils, the resulting pressure collapses the coil at those points and increases interlayer coil capacitance which in turn causes an even more bland sound. As with anything done by hand not much is consistent and the different staff attaching these wires squashed the coils to a different degree, the resulting differences in capacitance caused pickups to resonate at differing frequencies and thus sound different. It is generally believed the differences in sound of humbuckers was caused by imprecise coil winding which gave different pickups more or less than the specified 5000 turns. It has been said that the Leesona 102 coil winding machines that Gibson used at the time did not have rotation counters on them and the machines were stopped manually according to operator judgment and that caused differences in coil turns count. If that is true then these two factors combined to cause significant differences between coils.

Practically all humbuckers made by many different companies today have the same problem because they simply copy the original Gibson humbuckers, flaws and all.

Anyway, the coils will be wired in a certain series configuration that cancels hum but reinforces string signal in the same manner Electrovoice and the previous patent holders disclosed in their patents. Yes, this was certainly a cunning and elegant starting point, it is all coming together so well and he has just cause (although a little bit premature) to feel optimistic about the outcome. After all this seems like it is going to be a really elegant solution in so many ways.

After a day or two modifying the bobbins and assembling the first experimental prototype it is time to test the pickup in a guitar. It is an exciting and tense moment which turns to disappointment right away after his worst fears are confirmed, the sound is nothing like a P-90. It sounds very different since it doesn’t have the snap and impressions of piano mid-tones of a P-90. It is indistinct on the low notes (what we now know and refer to as being muddy or lacking mid tones that impart definition) compared to a P-90. But it does cancel hum and that is cause for some optimism.

In the ensuing days Seth tinkers with the experimental pickup trying different things to improve the sound. After all this is a beautifully simple design, it is based on an existing Gibson design (P-90) and all but two parts are already on hand and these are powerful reasons for persevering with it.

Seth gets the answer to his fears that the new pickup might not sound like a P-90, and try as he might he just can’t make it sound any better because he did not have an inductance meter or a Q meter to guide his tinkering. What he should have realized is his new pickup sounds like what a P-90 would sound like when the number of turns were reduced from 10,000 to approximately 5,000, because in effect that’s exactly what he had done. Remember that Law of Electrical Physics that operates in the side-by-side coils of a Humbucker? well it has raised it's ugly head again but Seth had no idea about how it played out in his Humbucker. Splitting the P-90 coils into two equal halves reduced the Mutual Inductance of a P-90 at 7 Henrys and Q3.2 to an unacceptable level of 4.4 Henrys and Q 2.5. Unfortunately Seth did not realize the subtractive effect of half-coils in series does not fully recover the great loss of inductance that had occurred when the P-90 coil was split in two identical halves. His half-coils inductance regime made the sound muddy and indistinct on the bottom end because of the inevitable broad low resonant peak. These factors gave the humbucker it’s distinctive sound which was quite unlike a P-90 which has a tall proud, well defined resonant peak. Having explored all avenues of adventure, or so he thought, he concluded it is as good as it is going to get and since he has no ideas of how to solve the hum problem with any method other than using 2 identical coils of half the parameters of a P-90 coil he begins winding down the project after a mere 2 weeks. Asymmetric dis-similar specialized coils were not even on the horizon back in 1955 but with their development circa 1996 a whole new era of hum canceling technology was born and some years later an authentic sounding P-90 that is hum canceling would emerge (more about that later).

To be perfectly clear about this Seth designed a clever pickup, but the technology necessary to fulfill it’s mission hadn’t been invented yet. It would be 57 years before the mysteries of the humbucker would be solved and a new Law of Electrical Physics would be discovered; a Law that practically every Electrical Engineer has no idea exists because the one place it manifests in is the side-by-side Humbucker guitar pickup and there are practically no Electrical Engineers designing pickups. And the ones that are invariably don’t have the imagination and inventive ability so solve problems like this one. More about that later.

Seth is in the final stages and there is one more problem about to surface. The new pickup needs a presentation cover. It is decided to make a cover from metal so it can be chrome plated for reasons of appearance. Flashy chrome is all the rage these days (remember what cars looked like back then …. lots of flashy chrome). Anyway brass is the obvious choice since it is not magnetic, it is malleable and can be deep drawn into the shape of a suitable cover. Before money is spent on Deep Draw tooling he makes a very rough prototype by hand. But when Seth fits the brass cover the sound suddenly becomes even worse, it loses even more definition and high frequencies. It is like someone speaking with hand over mouth.

Gretsch has obviously encountered the same phenomena and the way they got around it was to cut a H shaped section from the middle of the cover so the metal loop is limited to the perimeter of the pickup, away from the coils thereby lessening the unexplained dulling effect it had on the sound. The open top cover looked pretty cool too and so people thought they did that for appearance reasons.

The Filtertron is a great looking pickup, exceptional Industrial Artwork.

Scratching his head Seth seeks answers from his co-workers, the electrical engineers who work in Gibson’s amplifier design department. One particularly bright and knowledgeable engineer who knew a lot about transformer design suggests Eddy currents are the probable cause. And one way to reduce them is to find a suitable metal that inhibits Eddy currents. Seth consults the Engineers Handbook and discovers that the alloy Nickel-Silver has a relatively high electrical resistance. Nickel-Silver is close to home too because it’s the metal used to make fretwire. He then realizes P-90 Dog Ear covers are made of Nickel-Silver. He gets some sheet material from the people who make their Dog-Ear covers and hand makes a rough cover from the new material and fits it to the second prototype pickup to test it’s effect. Hurrah … he heard a big difference right away. There is a definite improvement in the sound compared to the brass cover but although it is greatly improved there remains a noticeable loss of clarity and high frequencies. But he decides the new cover is a good compromise solution and not bad enough to kill the project off, besides it has all that flashy chrome and that is a big marketing plus. Later on he considers cutting the top out of it but that was not an option because that would have made it look similar to a Gretsch Filtertron. So to add much needed decoration to it he stamps some imprints into the top of the cover to represent the hidden steel poles underneath. Later in the 1970’s players would take the covers off once it was discovered doing so improved high frequencies and clarity. Also after market pickup cover makers would make open top covers to fit Gibson humbuckers to improve the sound while still protecting the coils, and retain some of the chrome plating. Another notable improvement is a metal cover that has Zero impact on the sound and is not at all microphonic but that would be discoverd 60 years on.

In most ways it was all very convenient and elegant because the metal cover would hide the slug poles and the cover would have an unbroken top. This gave the pickup a desirably different appearance. Seth went one step further and mounted it in a P-90 Dog-Ear frame with two long screws and that allowed the pickup a lot of up and down adjustment, Gretsch’s humbucker had very little adjustment because it is mounted rigidly to the guitar and one is required to put shims under it to alter it’s proximity to the strings. However adjusting pickups was not something players did back then but Gibson realized it was a good idea to give the pickup a lot of application flexibility, it could be used in archtops as well as solid bodies with both carved tops and flat tops and could easily be adjusted to suit the guitar. Although Seth’s humbucker did cancel hum effectively it did not have the gorgeous piano tones, well defined focused bass and snappy attack of a P-90. That goal proved to be elusive even before the advent of the Nickel-Silver cover. Resigned to accepting the sonic limitations of the new humbucker Seth reports to Ted McCarty that Gibson have their new hum canceling pickup and forthrightly puts it on McCarty’s desk for his appraisal and he hoped, his approval, a mere 3 weeks after his brief.

At first McCarty is pleased that Gibson has a silent pickup but this soon wanes as he realizes the sound is not as good as the P-90, but he acknowledges that it is silent as far as hum is concerned. Being less than fully enthusiastic Gibson sat on the pickup for 2 years because of it’s rather uninteresting sound, believing it was not good enough to replace the charismatic P-90. However Gretsch has just released a humbucking pickup named a Filtertron, it stops 60Hz hum in it’s tracks and the advent of a silent pickup has caused great excitement among guitarists when Gretsch displayed their revolutionary humbucker at a Music Trades exhibition. Gibson salesmen were embarrassed and envious with this great technical advancement from Gretsch. In fact Gibson by this time had forgotten about it’s humbuckers and had to be reminded of it’s existence by Seth Lover who overheard conversations concerning Gretsch’s silent pickup.

Seth's prototype humbucker hand made in 1955 before Gibson's marketing men insisted on cosmetic changes.

The prototype pickup was found and presented for further consideration. However Gibson salesmen didn’t like the appearance of Seth’s pickup, they think is looks like it sounds, quite bland compared to the P-90 that is, and remember pickups in those days had to sound good at room volume since overdrive hadn’t been discovered yet … also Seth’s prototype didn’t have adjustable poles like the P-90 or Gretsch’s Filtertron. The Filtertron was a very interesting looking pickup, a minor work of industrial design art but Gibson could not be seen to copy Gretsch. The Gibson sales team insist Seth revisit his first prototype and put one row of pole screws to replace the steel slugs in one bobbin, giving it some visual relationship to a P-90. This immediately made the pickup look much more interesting with a somewhat asymmetrical appearance … and coincidentally, asymmetric coil performance. The asymmetric coil performance made the sound even more bland because the resonant peaks of the coils now occurred at different frequencies making the resonant peak of the sum of the coils flatter and broader which causes a further loss of character and loss of focus and tonal detail on the low strings. The salesmen were pleased because it had adjustable poles and overall height adjustment and it didn’t look like a Filtertron, but it sounded even more bland than Seth’s original prototype.

Of course the resultant asymmetry from using skinny screws poles in the primary coil and larger 3/16 inch steel slugs in the secondary coil also meant that the hum canceling properties of the pickup was somewhat compromised, but Gibson thought guitar players would not notice the small amount of hum because back in the late 1950’s high gain amplification had not been discovered and the amplification factor back then was not enough to make the hum prominent.

Gibson were feeling the pressure and had a time frame to consider, they had to deliver a silent pickup to the market to quell the growing discontent with the noisy P-90. The race was on and they had to do something to stop losing sales to Gretsch that were attributed to the noisy P-90. The powers that be within Gibson at that time weighed up the pros and cons. On the plus side the new pickup had been developed in record time at low cost to the company, had a very nice and interesting appearance, was fully adjustable and very versatile in application, was cheap to manufacture and all but three parts were already on hand. That meant very good economy because there were very few redundant parts left over from the P-90. On the con side was it didn’t produce the hoped for sound of a P-90. Although the new pickup fell short of producing P-90 sound it was decided that the sound was good enough in it’s own right and the pickup had a cool appearance and that it would be a job for Gibson’s marketing people to convince players to adapt to and accept the new sound by the power of marketing persuasion. Their Patent application had not been granted so a little Gold sticker bearing the words “Patent Applied For” was attached to the baseplate. Thus the Gibson humbucker with it’s sound downgraded from Seth’s original, ostensibly for appearance sake, entered service circa 1957 and over time guitar players did accept it because it produced sound without 60Hz hum and it was the only pickup Gibson offered on it’s high end models, the noisy P-90 having been relegated to pasture.

US Patent 2896491 was filed in Jun 22, 1955 and granted on Jul 28, 1959. However one has to wonder what was actually patented, humbucking coils were not novel because Lesti disclosed them in his patent 20,070 and so too did Knoblaugh in his 2,119,584. Me thinks its more about the construction and mechanical design. Whatever it was that was patented pleased the top brass at Gibson since there were valuable marketing gains in having a patent.

Let me at this point discuss assertions on Wikipedia and in other quarters that Gretsch beat Gibson to the punch. These are historical facts gleaned from actual patent application documents:-

• Seth Lovers Patent number: 2896491 Filing date: Jun 22, 1955 Granted: Jul 28, 1959 • J. R. Butts, Gretsch patent 2892371 filed Jan 22 1957 Granted: June 30 1959.

One has to wonder why it is that the Patent Office granted Ray Butts a patent because it is patently clear that Gibson filed for it’s patent almost 2 years before Gretsch and yet Gretsch’s patent was granted 1 month before Gibson’s was. One would have thought there was grounds for Gibson to have Gretsch’s patent invalidated. Gibson considered challenging Gretsch and applying to have it’s patent invalidated but upon realizing the Filtertron was electrically flawed more than their own and didn’t sound as good as Seth’s humbucker perhaps they decided to avoid expensive litigation and bad vibes knowing customers would prefer the bigger Gibson humbucker for it’s better sound. However, later it would emerge that Ray Butts had proved to the Patent Office that he had been working on his humbucker before Seth Lover got started and so the Patent Office allowed him a Patent on the doctrine of "He who invents first has priority". But that begs the question "Why was Seth Lover granted a patent for essentially the same device?" Perhaps it was the the loose language that was used in the single patent claim that had 5 parts.

For some unknown reason that excites the imagination Gibson didn’t want to reveal how their humbucker worked, they wanted to keep the technology they borrowed from Electrovoice and those earlier humbucking pickups a closely guarded secret. So, when their Patent was eventually granted in 1959, they stamped a false Patent number 2,737,842 on the baseplate of their pickups to prevent people from obtaining a copy of their patent application. US Patent 2,737,842 concerns a combined bridge and tailpiece assembly, awarded to one Lester Polfuss. I don’t know what Lester had to say about it but I suspect that violates Patent law. So what would be their defense if litigation was bought to bear on them by the Patent Office? Perhaps a clerical error in instructing the worker who made the number stamping tool? Whatever, they got away with it for the 16 year life span of the Patent and were never required to defend their ruse.

Gibson's humbucker as it was issued after Gibson's marketing men demanded cosmetic changes

with the resultant somewhat bland look compared to Gretsch's Fltertron which was a work of art.

The rest is history. Gibson’s humbucker graced many fine instruments, f-hole arch top models as well as solid body guitars ever since. It was many years later discovered by modern players that Gibson’s humbucker was invaluable when using high gain where otherwise hum would be highly undesirable. The broad low resonant peak also lent itself to modern high gain playing in other ways too, by providing a fat fluid flowing sound that comes into it’s own once the amp/speakers are cooking. Of course that was compared to Fender pickup because the P-90 had all but been forgotten in the passing of time with the emerging dominance of Gibson’s humbucker. Modern players have not been exposed to the P-90 so they had not experienced the wonderful whack attack and clarity of the low notes it produced and it’s versatility and dynamic range. For many years the most obvious choice was either a single coil Strat pickup or a Gibson humbucker. But Single coils are a whole nother story, and a very interesting one too. I’ll get to that another time.

Getting back to the main theme “What is the best humbucker?”

Well we have discovered flaws in Gibson type humbuckers and how the asymmetric under-wound coils with a low Q factor result in a lack of tone and clarity on the low wound strings from the neck pickup that also makes playing chords at high volume a toneless, messy, sloppy affair. We also learned it is not completely silent because it is a little electrically unbalanced and that the shiny Chrome plated cover contributes even more to the loss of focus and clarity and gives rise to microphonic feedback. Also remember the coils are squashed from the termination leads that contribute to these performance and sonic shortcomings. And so the obvious question arises “What can be done to improve these flaws?”

It seems Seth ran into a brick wall and his work was not really finished back in 1955 and he was not able to successfully overcome the problems. We now know that Seth would have had to abandon the idea that a hum-canceling version of the P-90 could be based on P-90 coil bobbins. It turns out that his approach was very flawed because it was glued to the P-90 so his goal of silencing the P-90 was never going to be solved with that approach, something radically different was required and Seth could not think far enough outside the box.

Although there are literally dozens and dozens of companies and individuals manufacturing humbuckers today it is abundantly clear that not one has the interest or means to solve these problems or even realize a problem exists, they simply copy Seths original design and their humbuckers inherit the same flaws. Some have explored different wire gauges and different number of turns, introduce gaps in the magnetic circuit, substitute Ferrite magnets for Alnico, substitute blade poles for screw poles and give their products alluring suggestive names that appeal to customer psychology and conjure up imagination of better sound. But that’s all they have done, there is no fundamental improvement to the design of the humbucker in doing those things. Claims of improvement are nothing more than marketing hype and buzz lingo such as scatter wound coils and they make millions every year recycling copies of the same old stuff.

The Gibson style humbucker’s design evolution has been more or less static since the day Seth handed in his project to Ted McCarty back in 1955, apart from the downgrade insisted on by Gibson’s marketing people. And as you will recall the whole design process was dictated by dimensional and mechanical criteria and the convenience of using parts on-hand from the P-90, there were no electrical experiments done to discover the best design of the coils and magnetic circuit. In fact Seth made some blunders with his pickup but

Interestingly, as mentioned before, Seth didn’t fully grasp the finer points of humbucking pickups as his patent reveals. His US Patent 2896491 disclosed several designs, one is the well known two bobbins side-by-side and is functional. However another is a sidewinder design and sidewinders are fundamentally flawed, the design is dysfunctional and lacking dynamics and mutual inductance which results in lack of bite, presence and drive on the plain strings. The fact that he included a sidewinder in his patent reveals Seth didn’t fully grasp the finer points of humbucking principle because any respectable Electrical Engineer would have dismissed it as a flawed dysfunctional design. Tellingly, Gibson only ever used Seth’s sidewinder design in one model Firebyrd guitar because it's sound was lacking, and the reason is was used for that model Firebyrd is anyones guess. However when Bill Lawrence was working at Gibson he found a use for the flawed sidewinder, in their EB series bass instruments. It’s that huge rectangular chrome pickup that hides 2 huge coils lying on their sides, the coils are excessively over-wound to the point of being utterly ridiculous. It is interesting that Bill Lawrence later claimed to be the inventor of the sidewinder during a personal discussion I had with him at a NAMM show circa 2000. He probably thought he would not be found out because Gibson’s actual patent number was never disclosed and so how would anyone be the wiser?

Looking back we now understand that the humbucker was never really perfected back in 1955 because Seth Lover didn’t have the resources or the time to solve the electrical engineering problems it had. So it stands to reason that someone with a lot more inventive experience and know-how in pickup design has to take up the challenge of reinventing and perfecting the humbucker to make it more suitable for modern high volume playing styles and make it sound better. It might even be a case of going back to the drawing board. But the problem is the current pickup industry is 98% populated by people who make millions by copying existing designs and who don’t understand the basic laws of physics, magnetism and electricity, go figure !!!!

Well it is circa 2006 and Seymour Duncan, having forged a friendship with Seth Lover, hits upon a brilliant marketing scheme. To consult with the man himself and create a line of Duncan branded authentic Seth Lover original humbuckers. In the meantime Seth had realized his coils were too small and when he designed the Wide Range humbucker for Fender he made the bobbins much bigger. Seth had learned size does matter in humbucking design but Seymour wasn’t interested and so the Seth Lover humbuckers made by Duncan sound no better than the original Gibson PAF, and maybe not as good. It is also very interesting that Seth didn’t like or approve of the changes to the poles that Gibson’s Marketing people demanded. It’s funny how marketing and money can be used to persuade people to believe in a convenient departure from the facts.

Remember the P-90 experienced a sudden death in 1957 with the advent of Gibson’s humbucker. As you will also remember that was because the P-90 produced a lot of hum, and that problem was never solved satisfactorily by Gibson, Seth Lover or any modern day pickup manufacturer. Sure they have their stacks like Gibsons P-100, Duncans Stacked P-90 and Fralins and Mojotone's sidewinder disguised under a P-90 cover but these are only P-90 look alikes, they certainly don’t sound like a real deal P-90. So the poor ole P-90 had been relegated to the back benches since 1957 in spite of it’s terrific and versatile sprongy sound. The hum it produces is it’s Achilles heel and that was it’s downfall.

That is until 2009 when myself, Chris Kinman, after nine years of inventive activity, unveiled my P-90 Hx. Hx is an acronym for Hum Cancelling and my P-90 Hx looks and sounds like an actual P-90 (well actually it sounds better IMHO). The reason it took 9 years is that the problems Seth Lover faced back in 1955 were of such magnitude they was unsolvable at that time because the technology did not exist … hadn’t been invented. Remember Seth was an engineer who borrowed heavily from Electrovoice and previous inventors for the hum canceling technique he used in his PAF humbucker. Seth didn’t invent the humbucking concept, he invented a way to make a humbucking pickup with a permanent magnet (not an electro-magnet) using existing humbucking techniques.

The solution to hum problems with the P-90 ultimately required some 206 individual components, complex and highly innovative design and sophisticated manufacturing. The Kinman P-90 Hx is a work of art, highly inventive technically, a modern marvel and a magnificent achievement. No other pickup comes even remotely close to it’s complexity and sonic performance and no other pickup designer / maker would wait 9 years to bring such a product to the market. I do not sell underdeveloped inferior versions as other pickup manufacturers do. Consider that a normal noisy P-90 has just 13 components and common stacks like the P-100 have a mere 22, then you will realize why Seth Lover could never have solved the hum problem and make a hum cancelling pickup that retained the magnificent luscious, versatile and bouncy sound of a P-90. For one, Gibson would not even consider making a pickup with 206 parts because of the very cost of manufacturing.

But what has this to do with humbuckers? Well remember there was a strong connection between P-90’s and humbuckers because back in 1955 Seth Lover based his humbucker on P-90 parts, it was meant to sound like a P-90 but he couldn’t do it. And ultimately I invented and patented the solution to the original problem with my highly complex invention I call the P-90 Hx.

3 years after accomplishing the impossible with my P-90 Hx I turned my attention to the humbucker. Drawing on my vast experience of understanding problems and then devising solutions to create great sounding hum canceling single coil pickups I also found ways of improving and perfecting the good ole humbucker.

My humbuckers, when used in the neck position, gives greatly improved clarity of low notes and chords at high volume, they have TONE. That alone should get your attention but I also claim they sound better than a conventional humbucker, describing the low and mid tones as piano like. Now that’s not a description used to describe humbuckers that you would have seen before.

So what is the best humbucker? To find out Navigate to >Products >Guitar >Humbuckers and take a look at the some 20 different models there. Each one is an engineering and sonic masterpiece.

The man himself, Seth came up with a pickup that would, in later years,

cause a storm among guitar players the world over.